PATENTS – COMMON PITFALLS AND HOW TO AVOID THEM – Chapter III

C1) Not considering infringement under the doctrine of equivalents

The concept of equivalence will be further explained with the following example.

Let’s imagine the independent claim of a patent is:

“Pedal-powered device comprising a saddle (A), a handlebar (B), a wheel (C) for its movement on a surface”.

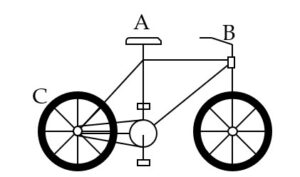

It is quite clear that the device schematized in the figure below represents an infringement of this claim.

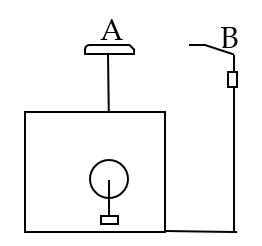

Instead, the device schematized in the following figure does not seem to incur in any infringements, as no wheel for its movement on a surface is present, and therefore no components that allows it to move:

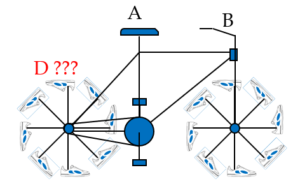

But what about the device shown in the following figure?

As you can see, it is a pedal-powered device that comprises a saddle, a handlebar, and “something” (D) for its movement on a surface; but is this “something” a wheel?

No, probably not, but it is to some extent similar to a wheel.

In these kinds of situations, in which one (or more) feature of a claim are not reproduced in a specific product (or method), but it is rather replaced by a similar feature, there could be infringement under the doctrine of equivalents, or infringement by equivalent.

Different states, and even different courts or judges within the same state, use different criteria to evaluate equivalence when compared to others; in Italy, the most common criteria are the FWR (Function, way, result) criterion, which essentially involves assessing whether the similar characteristic has the same function of the missing one and achieves the same result by operating in the same way, and the criterion of obviousness of the variant. Anyway, please note that this is not a comprehensive list: other criteria can also be used.

In this context, it is not possible to explain in detail all the different aspects of the equivalence matter, which could be considered as one of the most complicated in the world of patents, but when assessing whether a specific product or method reproduces the characteristics of a claim, the important thing is to understand that the absence from the product or method of the feature present in the independent claim is not sufficient to exclude infringement; in fact, it is always good to ask yourself whether the missing feature could be considered equivalent to a similar feature present in that product or method.

C2) Not considering indirect infringement

Indirect infringement typically occurs when there is a supply or offer for sale not of the patented invention (for example a bicycle with an innovative wheel), but rather of means related to the essential element (for example the innovative wheel) for the implementation of the patented invention, having knowledge (or being able to have it with ordinary diligence) of the suitability and destination of the means to implement the invention.

However, it should be noted that there is not indirect infringement when the available means consist of products that are currently to be found on the market, unless the third party incites the subject to whom the means are supplied to perform the prohibited acts, that is to say if there is an incitement to use such products in a patented solution.

In these cases, therefore, it becomes important what you communicate through advertising material, catalogues, brochures, instructions, etc., to avoid giving indications that could be considered as incitement to use specific products (a wheel) in a device protected by a patent (a specific innovative bicycle).

C3) Pay attention to advertising!

According to some legislations, by writing that a solution is protected by a patent when clearly it is not (or not yet), you can commit a crime.

In some legislations, when a patent application has not been granted yet, it is possible to write “patent pending” with respect to a product or method that uses the patented technology, but in other legislations (for example the German one) this is not allowed.

Bear in mind that, before placing this type of information on a product, it is important to consult a patent attorney or a local lawyer to check what the specific national legislation requires.

C4) Not monitoring your competitors

The monitoring of your competitors, both of their patents and their products, can be very useful from a patent perspective.

A periodic monitoring, for example every two or three months, of the patents published by your competitors (please note that patents are generally published eighteen months after the filing, and before that they are secret and therefore “invisible”) can help offset the intrinsic limits of the patent searches, such as, in addition to the invisibility during the secrecy period just mentioned, the fact that searches are generally carried out using keywords, and the keywords used for the search can be different with respect to the ones used for writing the patent you are looking for.

Furthermore, a periodic monitoring of the patents published by competitors gives you time to implement corrective actions; in fact, some actions aimed at revoking a patent, for example the opposition to a European patent, can only be carried out within a certain time after the grant of the patent, and others only before the grant (such as sending third party observations to the patent offices in order to try to prevent a patent from being granted).

Moreover, the periodic monitoring of published patents allows you to have an overview, albeit with a certain delay due to the period of secrecy, on the technological roadmaps of the competitors.

With regards to the monitoring of competitors’ products, it instead allows you to evaluate whether they are interfering with one of your patents and also to modify, when and if possible, your already filed but not yet granted patent applications, in order to better cover the competitors’ solutions.

C5) Lack of basic patent training in different company roles

Many people think that intellectual property, and in particular patents, only affect some specific business sectors and in particular the technical area, and so they conclude that providing a basic knowledge of these aspects to other business sectors is useless.

It is certainly true that product designers and developers should at least know some of the aspects of patent law, but many other business sectors may also face, even without knowing it, issues related to intellectual property, and in particular to patents.

Below you will find a list of the main patent activities that could/should involve the main corporate roles; in the previous points and chapter 1 and 2 of the present essay, you will find more details on the different activities.

R&D: Verify the freedom to operate (FTO) of the new solutions to be placed on the market; protect your innovations, regulate the property rights on inventions developed with third parties with whom you collaborate, etc.

PURCHASING OFFICE: ask/verify the FTO of the purchased solutions; define indemnity clauses in purchase contracts with reference to the risks associated to patent infringement; ensure the secrecy of the information exchanged with suppliers to preserve the novelty of one’s potentially patentable inventions; define the clauses of property rights on inventions developed by third parties and with third parties through development contracts, co-development, etc.

SALES: successfully negotiate any indemnity clauses requested by the clients relating to risks associated to patent infringement; preserve the secrecy of the exchanged information; define the clauses of property rights on inventions developed by third parties and with third parties through development contracts, co-development, etc.

MARKETING: convey the correct information (patented, patent pending, etc.) relating to patents in brochures, presentations, etc.; avoid publishing information that could put you at risk of indirect counterfeiting; preserve the secrecy of information, etc.

HR: verify that the employment contracts (both of employees and consultants) comply with the regulations relating to patents (for example by providing a remuneration for the inventions of the employees who are entitled to them); check the legislation and patent clauses in the contracts with non-employee collaborators, such as PhD students, interns, external collaborators, etc.; inform employees of the duties of secrecy related to the employment contract, possibly by signing an NDA, even in the event of termination of the employment relationship, etc.

We have reached the end of this journey on patents and related common pitfalls, and we hope the information we provided could help you become more aware while facing the complicated universe of patents, or at least it could make you think twice before carrying out actions that could lead to the loss of your own rights or the violation of third parties’ rights.

The Barzanò & Zanardo team is available to assist you in every phase of the protection of intellectual property rights.